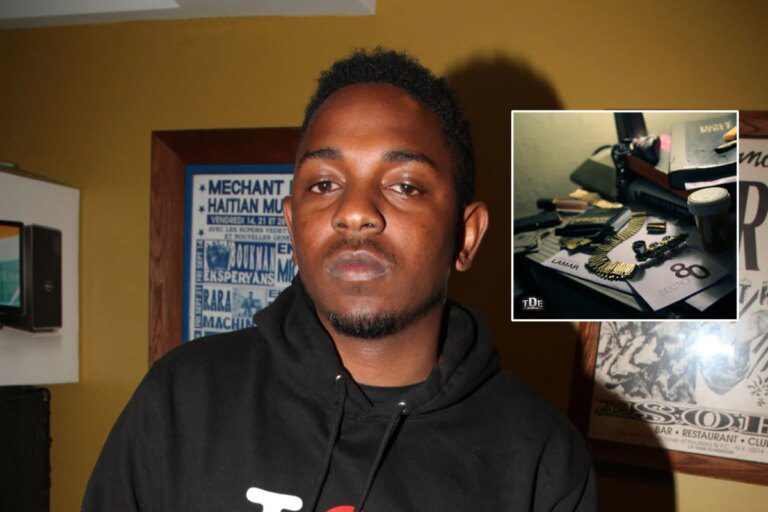

One of the greatest rappers of the Big 3 generation to influence hip-hop, Kendrick Lamar’s debut album Section.80 is a warning of things to come. K-Dot’s breakout project established him as not only a talented rapper, but the future voice of a generation.

In 2010, the Overly Dedicated mixtape introduced the world to a young Kendrick Lamar, a conflicted, hungry artist “trying to push over the edge.” Rather than continuing to rely on his raucous bars to establish rap dominance, as most hip-hop newcomers do, 2011’s Section.80 sought to elevate the conversation surrounding Kendrick’s talent. Kendrick used his Section.80 album as a megaphone to convey the struggles of black, poor millennials.

Section.80 explores institutional racism, nihilism, and even beauty standards that are toxic to women, but the key to its success is that it does it all while maintaining a healthy dose of swagger. Produced by then-unknowns THC and Sounwave, the production was set against the dusty jazz backdrop of Poltergeist or Digable Planets, although Kendrick grew up in California and was about to collaborate with Dr. Dre .

In “Poe Man Dreams (Hi Vice),” young Kendrick has spent his life trying to balance his drug addiction and break away from his worship of gang culture. However, the song’s grainy and ethereal background makes it a perfect fit for hot-loading whip. The best part is that the exhilarating arrangements in Section 80 encourage mass replay value, which in turn makes Kendrick’s reflective strips an even bigger hit.

“You know why we drugged babies/’Cause we were born in the ’80s,” Kendrick raps on “ADHD,” linking millennials’ rampant drug addiction to the impact of the drug epidemic on parents. “ADHD” became the album’s lead single and remains a calling card for his day one fans because it’s so catchy. The lyrics are a nod to the album’s title, which is a nod to Section 8 low-income housing and to those born in the 1980s. Kendrick was born in 1987.

With all these themes in mind, K-Dot also knows when to have some fun. On “Rigamortous,” Kendrick just lets off steam through some speakers, showcasing his tongue-twisting braggadocious nature and reminding listeners that he’s still in the hunt for hip-hop supremacy. Let’s also not forget that “Hol’ Up” is just a young, horned Kendrick who dreams of having sex with a flight attendant on a long-haul flight.

These brief moments and Kendrick’s transparency as host also help his bars sound less preachy. On album closer “HiiiPower,” Kendrick clarifies that he raps about sociopolitical issues not because he wants to, but because the civil rights movement showed him something he could no longer ignore.

“Martin Luther stared at my vision/Malcolm X put a spell on my future, someone caught me/I fell victim to a revolutionary song,” he raps.

It’s no surprise, then, that each album after Section.80 pushed Kendrick further into the role he had set for himself within the album’s themes. From “Good Kids” and “mAAd city” to “Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers,” each project has found Kendrick increasingly adept at conveying the black experience in refreshing ways. He excelled at it early on, so much so that by the time his second album, To Pimp a Butterfly, was released, he was thrust into hip-hop’s upper echelon. Everything he’s done since then (including his most recent appearance on The Pop Out in June) now seems to be entirely about service to his community.

Kendrick’s ballads have since resonated with millions, and in turn, the 2011 project that started it all has become a nostalgic, abrasive beacon for Kendrick’s closest supporters. It’s by no means a perfect album – Kendrick didn’t show up until “Damn”. In 2017, Section.80 showcased growth and experimentation as he became the most popular rapper in the world. It’s a throwback to a time when his bars were created specifically for people who shared his experiences. Thirteen years after its release, listening to Section.80 again is like having a beer with an old friend and reminiscing about the good times when it was just you and them.